Ahhh. Vacationing in paradise. You’ve left the rat race for a brief, blissful respite in one of the most beautiful places on Earth. What could go wrong? Unfortunately, plenty. We all tend to throw caution to the wind to some degree when it comes to vacationing. Sometimes it comes in the form of spending way more than you intended. (That one can hurt, but at least it just hits you in the wallet.) Other times, it comes in the form of a foolhardy decision to get a selfie on rocky shoreline during 40 foot surf. (That’s the epitome of the wrong place, wrong time.) There’s a lot that visitors should be aware of when exploring Hawaii’s natural wonders. Luckily, most everything that can hurt you here is easily avoidable, especially if you know what to expect and keep your trusty common sense at hand. This blog will focus on the things people will encounter in and around the ocean, while land-based hazards will be the topic of a future blog.

The Sun

Excluding our food prices, the hazard that affects by far the most people is the sun. Hawaii’s latitude means we receive sunlight that’s more directly overhead than anywhere on the mainland. (The more overhead the sunlight is, the less atmosphere it is filtered through, and it’s also more concentrated than it is farther north.) If you want to enjoy your entire vacation, our best advice is to cover up and wear a hat. At the very least make sure that you wear a strong sunscreen—every day, all day, even when it’s cloudy. We recommend a water-resistant sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30. Apply 30 minutes before exposure for the most effectiveness. Physical sunblocks (those containing zinc and/or titanium oxide—we try to use those with at least 20% zinc) are said to be more reef-safe than chemical sunblocks, which are more common but are banned from sale and use in Hawaii. Many visitors who get burned do so while snorkeling. You likely won’t feel it at first because you’re in the water. We strongly suggest that you wear a long-sleeved rash guard (consider one with a hood) while snorkeling, or you may get a nasty surprise. Try to avoid the sun between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. since the sun’s rays are particularly strong during this time. If you are fair-skinned or unaccustomed to the sun and want to lay out, 15–20 minutes per side is all you should consider the first day. You can increase it a bit each day. Beware of the fact that Hawaii’s ever-constant trade winds will hide the symptoms of a burn until it’s too late. You may find that trying to get your tan as golden as possible isn’t worth it; tropical suntans are notoriously short-lived, whereas you are sure to remember a bad burn far longer. If, after all our warnings, you still get burned, aloe vera gel works well to relieve the pain. (Some gels also come with lidocaine in them.) Ask your hotel front desk if they have any aloe plants on the grounds. Peel the skin off a section and make several crisscross cuts in the meat, then rub the plant on your skin. Oooo, it’ll feel so good!.

Excluding our food prices, the hazard that affects by far the most people is the sun. Hawaii’s latitude means we receive sunlight that’s more directly overhead than anywhere on the mainland. (The more overhead the sunlight is, the less atmosphere it is filtered through, and it’s also more concentrated than it is farther north.) If you want to enjoy your entire vacation, our best advice is to cover up and wear a hat. At the very least make sure that you wear a strong sunscreen—every day, all day, even when it’s cloudy. We recommend a water-resistant sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30. Apply 30 minutes before exposure for the most effectiveness. Physical sunblocks (those containing zinc and/or titanium oxide—we try to use those with at least 20% zinc) are said to be more reef-safe than chemical sunblocks, which are more common but are banned from sale and use in Hawaii. Many visitors who get burned do so while snorkeling. You likely won’t feel it at first because you’re in the water. We strongly suggest that you wear a long-sleeved rash guard (consider one with a hood) while snorkeling, or you may get a nasty surprise. Try to avoid the sun between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. since the sun’s rays are particularly strong during this time. If you are fair-skinned or unaccustomed to the sun and want to lay out, 15–20 minutes per side is all you should consider the first day. You can increase it a bit each day. Beware of the fact that Hawaii’s ever-constant trade winds will hide the symptoms of a burn until it’s too late. You may find that trying to get your tan as golden as possible isn’t worth it; tropical suntans are notoriously short-lived, whereas you are sure to remember a bad burn far longer. If, after all our warnings, you still get burned, aloe vera gel works well to relieve the pain. (Some gels also come with lidocaine in them.) Ask your hotel front desk if they have any aloe plants on the grounds. Peel the skin off a section and make several crisscross cuts in the meat, then rub the plant on your skin. Oooo, it’ll feel so good!.

The Ocean

The most serious hazard in Hawaii is the surf. Though more calm in the summer and on the leeward sides of the islands, high surf can be found anywhere on the islands, at any time of the year. The sad fact is that more people drown in Hawai‘i each year than anywhere else in the country. This isn’t said to keep you from enjoying the ocean, but rather to instill in you a healthy respect for Hawaiian waters. Most mainlanders are unprepared for the strength of Hawai‘i’s surf. We’re out in the middle of the biggest ocean in the world, and the surf has lots of room to build up. We have our calm days when the water is like glass. We often have days where the surf is moderate, calling for respect and diligence on the part of the swimmer. And we have the high surf days, perfect for sitting on the beach, watching the experienced and the audacious tempt the ocean’s patience. Knowing the weather, surf forecast and tides are all important tools in keeping yourself out of harm’s way.

Other hazards include rip currents, which can form, cease and form again with no warning. If you get caught in a rip current, don’t fight and try to swim against it. You’ll only tire yourself out. You want to focus on staying afloat (rip currents don’t pull you under, they pull you away from shore) and swimming out of the current by swimming parallel to shore. By following the shore, you’ll eventually break free from the current. You can then follow the breaking waves back toward shore, approaching at an angle. Large “rogue waves” can come ashore with no warning. These usually occur when two or more waves fuse at sea, becoming a larger wave. There is a lot of rocky shoreline that features tide pools, blowholes, arches or caves that can be fun to explore. It’s in these areas that high surf and rogue waves are especially dangerous—it only takes six inches of flowing water to knock you off your feet. Even calm seas are no guarantee of safety. Many people have been caught unaware by large waves during ostensibly “calm seas.” Everyone that grows up in Hawaii is taught to “never turn your back on the ocean”.

Other hazards include rip currents, which can form, cease and form again with no warning. If you get caught in a rip current, don’t fight and try to swim against it. You’ll only tire yourself out. You want to focus on staying afloat (rip currents don’t pull you under, they pull you away from shore) and swimming out of the current by swimming parallel to shore. By following the shore, you’ll eventually break free from the current. You can then follow the breaking waves back toward shore, approaching at an angle. Large “rogue waves” can come ashore with no warning. These usually occur when two or more waves fuse at sea, becoming a larger wave. There is a lot of rocky shoreline that features tide pools, blowholes, arches or caves that can be fun to explore. It’s in these areas that high surf and rogue waves are especially dangerous—it only takes six inches of flowing water to knock you off your feet. Even calm seas are no guarantee of safety. Many people have been caught unaware by large waves during ostensibly “calm seas.” Everyone that grows up in Hawaii is taught to “never turn your back on the ocean”.

I swam and snorkeled all of the beaches described in my guides on many occasions through the years. But beaches change. The underwater topography changes throughout the year. Storms can take a very safe beach and rearrange the sand, turning it into a dangerous beach. Just because I (or anyone else) describe a beach as being in a certain condition does not mean it will be in that same condition when you visit it. A few of the standard safety tips apply. Never turn your back on the ocean. Never swim alone. Never swim in the mouth of a river. Never swim in murky water. Never swim when the seas are not calm. Don’t walk too close to the shore break; a large wave can come and knock you over and pull you in. Observe ocean conditions carefully. Don’t let small children play in the water unsupervised. When you are in the ocean, fins give you far more power and speed and are a much under appreciated safety device (besides being more fun). If you are comfortable in a mask and snorkel, they provide considerable peace of mind, in addition to opening up the underwater world. Lastly, don’t let Hawaii’s idyllic environment cloud your judgment. Recognize the ocean for what it is: a powerful force that needs to be respected. A great resource that covers more of these tips in greater detail can be found at SafeBeachDay.com.

I swam and snorkeled all of the beaches described in my guides on many occasions through the years. But beaches change. The underwater topography changes throughout the year. Storms can take a very safe beach and rearrange the sand, turning it into a dangerous beach. Just because I (or anyone else) describe a beach as being in a certain condition does not mean it will be in that same condition when you visit it. A few of the standard safety tips apply. Never turn your back on the ocean. Never swim alone. Never swim in the mouth of a river. Never swim in murky water. Never swim when the seas are not calm. Don’t walk too close to the shore break; a large wave can come and knock you over and pull you in. Observe ocean conditions carefully. Don’t let small children play in the water unsupervised. When you are in the ocean, fins give you far more power and speed and are a much under appreciated safety device (besides being more fun). If you are comfortable in a mask and snorkel, they provide considerable peace of mind, in addition to opening up the underwater world. Lastly, don’t let Hawaii’s idyllic environment cloud your judgment. Recognize the ocean for what it is: a powerful force that needs to be respected. A great resource that covers more of these tips in greater detail can be found at SafeBeachDay.com.

Ocean Critters

Hawaiian marine life, for the most part, is quite friendly. There are, however, a few notable exceptions. (I don’t list coral here, since it is us that is biggest hazard to coral. Touching coral, either accidentally or by walking on it is far more damaging to the it than us. Also, we don’t have fire coral in Hawaii.) Here is a list of some critters that you should be aware of. This is not mentioned to frighten you out of the water. The odds are overwhelming that you won’t have any trouble with any of the beasties listed below. But should you encounter one, this information should be of some help.

Hawaiian marine life, for the most part, is quite friendly. There are, however, a few notable exceptions. (I don’t list coral here, since it is us that is biggest hazard to coral. Touching coral, either accidentally or by walking on it is far more damaging to the it than us. Also, we don’t have fire coral in Hawaii.) Here is a list of some critters that you should be aware of. This is not mentioned to frighten you out of the water. The odds are overwhelming that you won’t have any trouble with any of the beasties listed below. But should you encounter one, this information should be of some help.

Snorkeling

Ko Olina Ocean Adventures: Sunrise Snorkel Sail

Ko Olina Ocean Adventures offers 3-hour trips on their sailing catamaran including a hearty meal after the second snorkel stop. They also provide a 2-hour sunset sail featuring light appetizers and three adult beverages ($5 each for additional drinks).

North Shore Catamaran Charters: 4-hour snorkel sail

North Shore Catamaran offers summer snorkel trips from June to September. Their 4-hour snorkel trip guides you through a marine sanctuary, ensuring no touching of the sea life. They also offer a 2-hour sunset cruise year-round, featuring stunning views and a fun crew.

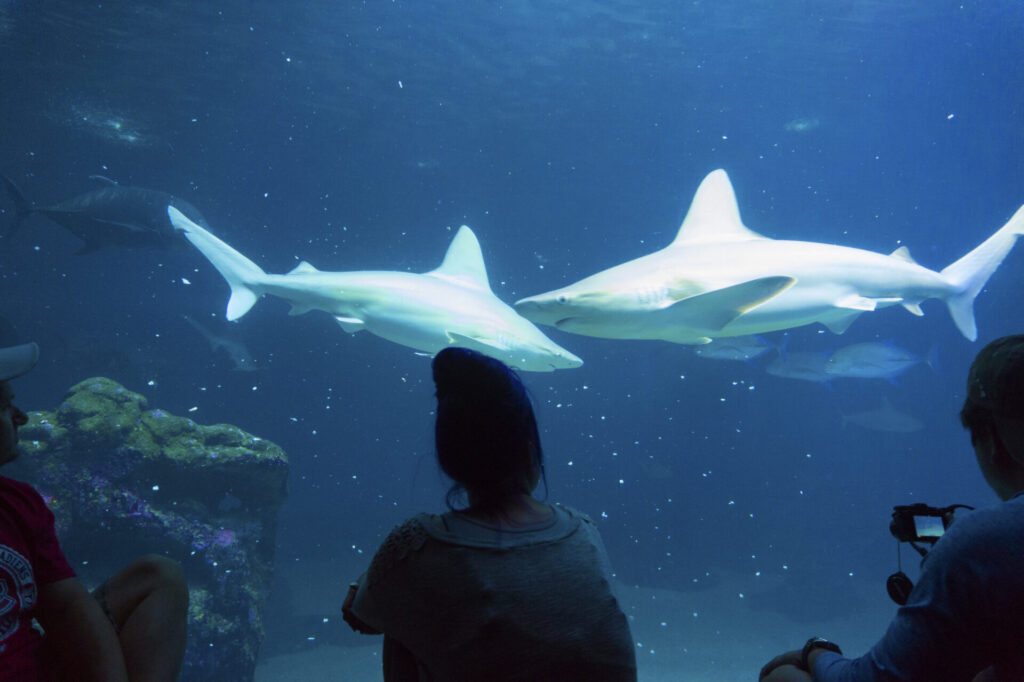

Hawai‘i does have sharks. Most are the essentially harmless white-tipped reef sharks, plus the occasional hammerhead or tiger shark. Contrary to what most people think, sharks live in every ocean and don’t pose the level of danger people attribute to them. Shark attacks are rare in Hawaii, averaging less than one per year over the decades, and fatalities are extremely uncommon. Considering the number of people who swam in our waters during that time, you are statistically more likely to get mauled by a hungry timeshare salesman than be bitten by a shark. If, in the rare instance that you happen to come upon a shark, however, swim away slowly. This kind of movement doesn’t interest them. Don’t splash about rapidly. Doing so makes you look like a fish in distress, which is appealing to sharks. The one kind of water you want to avoid is murky water, such as that found in river mouths. Most shark attacks occur in murky water at dawn or dusk since sharks are basically cowards who like to sneak up on their prey. In general, don’t worry about sharks. Any animal can be threatening. (Even Jessica Alba was once rudely accosted by an overly affectionate male dolphin.)

Box Jellyfish are one of the most common hazards in Hawaiian waters. Like clockwork, they come near leeward shores about 7–10 days after each full moon each month to spawn. They’re more prevalent around O‘ahu, but all islands get them to some degree. They’re next to impossible to spot in the water—you’re more likely to feel the sting than see them. Treatment is the same for Portuguese Man-of-War; vinegar’s the best remedy. Luckily they aren’t as painful, though individual results may vary. Stings can range from a fleeting, itchy pain to burning welts. Wetsuits or long-sleeved rash guards are your best bet for preventing stings. Portuguese Man-of-War are related to jellyfish but are unable to swim. They are instead propelled by a small sail and are at the mercy of the wind. Though small, they are capable of inflicting a painful sting. This occurs when the long, trailing tentacles are touched, triggering hundreds of thousands of spring-loaded stingers, called nematocysts, which inject venom. The resulting burning sensation is usually very unpleasant but not fatal. Though small, these cnidarians pack a real punch. When they do come ashore, they usually do so in great numbers, jostled by a strong storm offshore, and usually land on north-facing beaches. If you see them on the beach, don’t go in the water. If you do get stung, immediately remove the tentacles with a gloved hand, stick or whatever is handy and rinse thoroughly with vinegar to remove any adhering nematocysts. Then immerse in hot water or apply a hot pack for 45 minutes. If the condition worsens, see a doctor. The folk cure is urine, but you might look pretty silly applying it.

Box Jellyfish are one of the most common hazards in Hawaiian waters. Like clockwork, they come near leeward shores about 7–10 days after each full moon each month to spawn. They’re more prevalent around O‘ahu, but all islands get them to some degree. They’re next to impossible to spot in the water—you’re more likely to feel the sting than see them. Treatment is the same for Portuguese Man-of-War; vinegar’s the best remedy. Luckily they aren’t as painful, though individual results may vary. Stings can range from a fleeting, itchy pain to burning welts. Wetsuits or long-sleeved rash guards are your best bet for preventing stings. Portuguese Man-of-War are related to jellyfish but are unable to swim. They are instead propelled by a small sail and are at the mercy of the wind. Though small, they are capable of inflicting a painful sting. This occurs when the long, trailing tentacles are touched, triggering hundreds of thousands of spring-loaded stingers, called nematocysts, which inject venom. The resulting burning sensation is usually very unpleasant but not fatal. Though small, these cnidarians pack a real punch. When they do come ashore, they usually do so in great numbers, jostled by a strong storm offshore, and usually land on north-facing beaches. If you see them on the beach, don’t go in the water. If you do get stung, immediately remove the tentacles with a gloved hand, stick or whatever is handy and rinse thoroughly with vinegar to remove any adhering nematocysts. Then immerse in hot water or apply a hot pack for 45 minutes. If the condition worsens, see a doctor. The folk cure is urine, but you might look pretty silly applying it.

Sea Urchins are like living pin cushions. If you step on one or accidentally grab one, remove as much of the spine as possible with tweezers. After they are out, soak the wound in warm vinegar. See a physician if necessary. Coral skeletons are very sharp and, since the skeleton is overlaid by millions of living coral polyps, a scrape can leave proteinaceous matter in the wound, causing infection. This is why coral cuts are frustratingly slow to heal. Immediate cleaning and disinfecting of coral cuts should speed up healing time.

This far from being a comprehensive list of ocean hazards around Hawaii. Every beach, shoreline and snorkel spot is different. We go into even more detail in our continuously updated guides. I let you know the daily surf conditions for each beach described and more. Check out our believable guides so you can plan an unbelievable vacation.

0 Comments